Biography of Charles de Foucauld

1. A child from a Christian home (1858 to 1873)

2. A young man in a world without God (1874 to 1876)

3. An unconvinced military man (1876 to 1882)

4. A Serious Traveller (1882 to 1886)

5. A seeker of God (1886 to 1890)

6. A Trappist Monk (1890 to 1897)

7. Hermit in Jesus’ Land (1897 to 1900)

8. Brother to All in Beni Abbès (1901 to 1904)

9. A Friend to the Tuaregs (1904 to 1916)

1. A child from a Christian home (1858 to 1873)

2. A young man in a world without God (1874 to 1876)

3. An unconvinced military man (1876 to 1882)

4. A Serious Traveller (1882 to 1886)

5. A seeker of God (1886 to 1890)

6. A Trappist Monk (1890 to 1897)

7. Hermit in Jesus’ Land (1897 to 1900)

8. Brother to All in Beni Abbès (1901 to 1904)

9. A Friend to the Tuaregs (1904 to 1916)

1. A child from a Christian home (1858 to 1873)

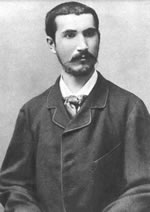

Charles was born in Strasbourg, France on September 15 1858 and was baptized two days after his birth.

“My God, we should all sing your mercies: Son of a holy mother, I learned from her to know you, to love you and to pray to you. Was not my first memory the prayer she made me recite morning and evening: ‘My God, bless father, mother, grandfather, grandmother, grandmother Foucauld and my little sister’?...”

But his mother, father and paternal grandmother all died in 1864. The grandfather took the two children, Charles (6 yrs) and Marie (3 yrs) into his home.

“I always admired the great intelligence of my grandfather whose infinite tenderness enveloped my childhood and youth with an atmosphere of love, whose warmth I still can feel.”

On April 28 1872, Charles made his first Holy Communion. He was confirmed the same day.

2. A young man in a world without God (1874 to 1876)

Charles was intelligent and studies were not difficult for him. He loved books, but read anything he could lay his hands on.

“If I worked a little in Nancy it was because I was allowed to mix in with my studies a host of readings that gave me a taste for studying but which did me the harm that you know…”

Little by little Charles distanced himself from his faith. He continued to respect the Catholic religion but he no longer believed in God.

“I remained twelve years without denying or believing anything, despairing of the truth and not even believing in God. There was no convincing proof.”

“At 17 I was totally selfish, full of vanity and irreverence, engulfed by a desire for what is evil. I was running wild.”

“I was in the dark. I no longer saw either God or men: There was only me.”

3. An unconvinced military man (1876 to 1882)

After two years of studies at Military College, Charles became an officer. His grandfather had just died and Charles inherited everything. He was 20 years old.

For several years, Charles would seek his pleasure in food and parties. At that time he was called “Fats Foucauld”.

“I sleep long. I eat a lot. I think little.”

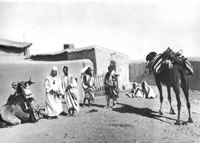

But in October 1880, Charles was sent to Algeria. He liked the country and the inhabitants interested him:

“The vegetation is superb: palm trees, laurel bushes, orange trees. It is a beautiful country! For my part, I was enthralled. In the midst of them all there are Arabs in white burnouses or dressed in bright colours, with a crowd of camels, small donkeys and goats, which have the most picturesque effect.”

However Charles’ refusal to listen to his superiors in an affair involving a woman eventually cost him his employment.

Having only just returned to France, he learned that his regiment was being sent to Tunisia:

“An expedition of this kind is too rare a pleasure to let it slip by without trying to enjoy it. I was indeed sent back to Africa, as I had requested but not quite in the regiment that I had wanted. I was part of a column which manoeuvred on the high plateaux, to the South of Saïda. It was a lot of fun. I enjoyed camp life as much as I disliked garrison life. I hope that the column will last a long time. When it is finished, I will try to go somewhere else where there is action.”

In January 1882, the columns were disbanded and Charles was again back in the barracks.

“I hate garrison life…I much prefer to take advantage of being young in order to travel. At least in that way I will be able to learn something and not waste my time.”

On January 28 1882 he resigned from the army.

4. A Serious Traveller (1882 to 1886)

Charles then decided to settle in Algiers in order to prepare his trip.

“It would be a shame to undertake such wonderful trips foolishly and like a simple tourist. I want to do them seriously, bringing along books in order to discover as thoroughly as possible both the ancient and modern history, though mostly the ancient history of all the countries through which I will be travelling.”

Morocco was not far away but was forbidden to Europeans. Charles was attracted to this little known country. After a long preparation of 15 months, he left for Morocco with a Jew named Mordechai who would serve as his guide.

“In 1883 Europeans could travel visibly and safely only in that territory which came under the Sultan’s rule. They could only enter the rest of Morocco if they were disguised, and even then it was at the risk of their lives. They were considered spies and would be killed if recognized. Nearly my entire trip was made in the independent parts of the country. I disguised myself from Tangiers onwards, so as to avoid awkward meetings. I pretended I was an Israelite. During my trip, my costume was that of Moroccan Jews, my religion, theirs, my name, Rabbi Joseph. I prayed and I sang in the Synagogue. Parents pleaded with me to bless their children…”

“To those who wanted to know where I was from, sometimes I responded Jerusalem, sometimes Moscow, and sometimes Algiers.”

“If someone were to ask the reason for my trip? To Muslims I would reply that, I was a mendicant rabbi going begging from town to town; To Jews, a pious Israelite who had come to Morocco despite the fatigue and danger, so as to inquire about the condition of his brothers.”

“My whole itinerary was recorded with readings from a compass and barometer.”

“As I walked along, I always had a notebook measuring 5 square centimetres in the palm of my left hand and a 2 centimetre long pencil in the other. I jotted down anything noteworthy along the road, what one could see to the right and the left. I noted changes in direction along with the compass reading; altitude changes along with the barometric height; the hour and the minute of each observation; the places where we stopped; the speed at which we walked etc. I wrote like this during most of the journey and all of the time when we were changing altitude.”

Nobody ever noticed this, even in the biggest caravans. I was careful to walk in front or behind my companions, so that with the help of the wide span of my clothes, they hardly saw the light movement of my hands. Thus the description and survey of my itinerary filled a good number of small notebooks.”

“As soon as I arrived in a village where it was possible for me to have a separate room, I completed them and copied them into notebooks which made up the journal of my trip. I spent my nights doing this.”

During my short stay in Tisint, I got to know several people: all the hajjis wanted to see me. The simple fact that I came from Algeria, where they had received a warm reception meant that I received the same welcome. I have since found out that several suspected that I was a Christian. They did not say a word, understanding perhaps better than I, what danger might befall me were they to speak up.”

“On arriving in Agadir, I went to the home of Hadj Bou Rhim. I cannot praise him enough nor articulate what I owe him. For me he proved to be the most reliable, most altruistic and most devoted of friends. On two occasions he risked his life in order to protect mine. He soon guessed that I was a Christian. Afterwards I told him so myself. Showing him such confidence only increased his attachment.”

For 11 months, Charles often received insults and stones. Several times he was almost killed.

On May 23 1884, a poor beggar arrived at the Algerian border crossing. He was barefoot, thin and covered with dirt. This poor Jew was none other than Charles de Foucauld.

“It was hard, but very interesting, and I succeeded!”

The scientific world of the time was greatly impressed by Charles’ work: a true exploration! He had travelled 3000 km in an almost unknown country. It was glory!

5. A seeker of God (1886 to 1890)

Such glory meant nothing to Charles. He left Algeria and settled in Paris, close to his family. He was 28 years old.

“At the beginning of October of the year 1886, after six months of family life, while in Paris getting my journey to Morocco published, I found myself in the company of people who were highly intelligent, highly virtuous and highly Christian. At the same time, an extremely strong interior grace was pushing me. Even though I wasn’t a believer I started going to Church. It was the only place where I felt at ease and I would spend long hours there repeating this strange prayer: “My God, if you exist, allow me know you!”

“But I did not know you…”

“Oh! My God, how much your hand was upon me and yet how little I was aware of it! How good you are! How good you are! How you protected me! How you covered me with your wings when I did not even believe in your existence!”

“Circumstances obliged me to be chaste. It was necessary so as to prepare my soul to receive the truth: the demon too easily masters a soul that is not chaste.”

“At the same time you led me back to my family where I was received like the prodigal son.”

“All this was your work, my God, your work alone…A beautiful soul assisted you, but by her silence, her gentleness, her goodness, her perfection…you attracted me by the beauty of this soul.”

“You then inspired me with this thought: ‘Since this soul is so intelligent, the religion in which she believes cannot be folly. So let me study this religion: let me take a professor of the Catholic religion, a wise priest, and let me see what it is about and if I should believe what it says.”

“So I then spoke to Fr. Huvelin. I asked for religious lessons: he made me kneel down and made me go to confession, and sent me to communion right away…”

“If there is joy in heaven over one sinner who is converted, there was joy when I went into this confessional!”

“How good you have been! How happy I am!”

“I who had doubted so much did not believe everything in a day; sometimes the miracles in the Gospel seemed hard to beleive; sometimes I wanted to mix passages from the Koran in with my prayers. But divine grace and the advice of my confessor dissipated the clouds…”

“My Lord Jesus, you have put into me this tender and growing love for you, this taste for prayer, this faith in your Word, this deep feeling of the duty of almsgiving, this desire to imitate you, this thirst to make the greatest sacrifice for you that I can make.”

“I wanted to be a religious and live only for God. My confessor made me wait three years.”

“The pilgrimage to the Holy Land, what a blessed influence it had on my life, although I did it in spite of myself, out of pure obedience to Fr. Huvelin …”

“After spending Christmas of 1888 in Bethlehem, having heard Midnight Mass and received Holy Communion in the Holy Grotto, at the end of two or three days, I returned to Jerusalem. The enchantment that I felt praying in this grotto which had resounded to the voices of Jesus, Mary and Joseph was indescribable.”

“I greatly thirst to lead the life that I glimpsed while walking in the streets of Nazareth, streets which had been trod by the feet of Our Lord, an unknown poor workman lost in abjection…”

6. A Trappist Monk (1890 to 1897)

Charles was very attached to his family and friends, but he felt called to leave everything so as to follow Jesus. On January 15 1890, he entered the Trappists.

“The Gospel showed me that the first commandment is to love God with all one’s heart and that we should enfold everything in love; everyone knows that the first effect of love is imitation. It seemed to me that nothing presented this life better than the Trappists.”

“Every person is a child of God who loves them infinitely: it is therefore impossible to want to love God without loving human beings: the more one loves God, the more one loves people. The love of God, the love of people, is my whole life; it will be my whole life I hope.”

Charles was happy as a Trappist. He learned a lot. He received a lot. But something more was missing.

“We are poor in material goods, but not as poor as was our Lord, not as poor as I was in Morocco, not as poor as St. Francis.”

“I love our Lord Jesus Christ and I cannot bear to lead a life other than his. I do not want to travel through life first class when the One that I love went in the lowest class.”

“I wondered if seeking out a few souls with whom one could form the beginning of a little congregation wasn’t called for.”

“The aim would be to lead a life as exactly like the life of our Lord as possible: living only by the work of one’s hands, following to the letter his counsels…”

“On top of this kind of work there would be a lot of prayers, the formation of small groups alone and the extension to mostly non-Christian countries which are so abandoned and where it would be so good to increase the love of Our Lord Jesus and the number of his servants.”

7. Hermit in Jesus’ Land (1897 to 1900)

On January 23 1897, the Superior General of the Trappists announced to Charles that he could leave the Trappe so as to follow Jesus, the poor workman of Nazareth.

Charles left for the Holy Land. He arrived in Nazareth where the Poor Clares took him in as a servant.

“God enabled me to find what I was looking for: the imitation of what was the life of Our Lord Jesus in the very same Nazareth…”

“In my wooden plank hut and at the foot of the Poor Clares’ Tabernacle, through my days of work and my nights of prayer, I had all that I had been looking for, so that it was clear that God had prepared this place for me.”

But Charles wanted to share this life of Nazareth with other brothers. This is why he wrote the Rule of the Little Brothers.

“I wanted to compose a very simple rule, apt to give to a few pious souls a family life around the Sacred Host.”

“My rule is so closely linked to the cult of the Holy Eucharist that it cannot be followed by a group without there being a priest among them and a tabernacle; it is only when I am a priest and there is an oratory around which we can come together, that I will be able to have a few companions.”

In August 1900, Charles returned to France. Fr. Huvelin was in agreement that he be ordained a priest.

“I went to spend a year in a convent. I studied and received Holy Orders there. I have been a priest since last June and I felt called straight away to go to the “lost sheep”, to the most abandoned, the most needy, so as to fulfil the commandment of love towards them: Love others as I have loved you, this is how you will be recognized as my disciples”. Knowing by experience that no people were more abandoned than the Muslims of Morocco and the Algerian Sahara, I requested and obtained permission to go to Beni Abbès, a little oasis in the Algerian Sahara on the boarders of Morocco”

8. Brother to All in Beni Abbès (1901 to 1904)

On October 28 1901, Charles arrived in Beni Abbès.

“The Natives made me perfectly welcome and I am forming relationships with them, trying to do them a little good.”

“The soldiers set about building me a chapel, three cells and a guest room out of dry bricks and palm tree trunks.”

“I want all the inhabitants to get used to looking on me as their brother, the universal brother…They are beginning to call the house “the fraternity”, and I find this very touching”

Each day, Charles spent hours before the Tabernacle.

“The Eucharist is Jesus, it is all of Jesus.”

“When you love, you feel like speaking the whole time with the one you love, or at least you want to look at him without ceasing. Prayer is nothing else. It is the familiar meeting with our Beloved. We look at Him, we tell Him we love Him, we rejoice to be at His feet.”

But there was constant knocking at the door. “Whatsoever you do to one of these little ones you do to me”. The Gospel had already transformed Charles’ life and he would straight away open the door to welcome the Beloved.

“From 4.30 am to 8.30 pm, I never stop talking and receiving people: slaves, the poor, the sick, soldiers, travellers and the curious.”

In this region, Charles discovered slavery. He was scandalized.

“When the government commits a grave injustice against those for whom we are in a certain measure responsible, we should tell them about it, for we do not have the right to be “sleeping watchmen,” “mute dogs” or “apathetic shepherds.”

The fraternity was built, but Charles waited for brothers to come.

“Pray to God so that I may do the work he has given me to do here: that I may establish a little convent of fervent and charitable monks, loving God with all their heart and their neighbour as themselves; a Zaouia of prayer and hospitality where such piety radiates that the whole country is illumined and warmed by it; a little family imitating so perfectly the virtues of JESUS that all who live in the surrounding area begin to love JESUS!”

But the brothers did not come.

“I am still alone. Several people have let me know that they would like to join me, but there are difficulties, the main one being the ban imposed by civic and military authorities on any Europeans travelling in the region because of the lack of security”.

In June 1903, the Bishop of the Sahara spent several days in Beni Abbés. He came from the South where he had visited the Tuaregs. Charles felt attracted by these people who live in the heart of the desert. There were no priests available to go there, so Charles volunteered.

“For the sake of spreading the holy Gospel I am ready to go to the ends of the earth and to live until the final judgement…”

“My God, may all people go to heaven!”

9. A Friend to the Tuaregs (1904 to 1916)

On January 13 1904, Charles left to go live with the Tuaregs.

Departure from Akabli with Commander Laperrine so as to accompany him on his expedition. His intention is to visit newly conquered peoples and to then push on as far as Timbuktu…”

“My vocation normally involves solitude, stability and silence. But if I believe that, as an exception, I am sometimes called to something else, like Mary I can only say, ‘I am the handmaid of the Lord’.”

“For the moment I am a nomad, going from camp to camp, trying to build up familiarity, trust and friendship. This nomadic life has the advantage of allowing me to see a lot of people and get to know the country.”

“The country almost always lacks water and pasture land and so the Tuaregs have to break up into small groups and spread out so as to feed and water their flocks. They live in very small groups, a tent here, a few tents there. You find them almost everywhere but they are very rarely together.”

“For a long while I had been asking JESUS to be, out for love of him, in like conditions, as far as comfort goes, to those in which I was in Morocco for my pleasure. The set up here is the same thing.”

“Today, I have the joy of reserving the Blessed Sacrament in a tabernacle for the first time in Tuareg land.”

“Sacred Heart of Jesus, thank you for this first tabernacle in Tuareg land! May it be the prelude to others and the announcement of the salvation of many souls! Sacred Heart of Jesus, radiate from the depths of this tabernacle on the people who are around you without knowing you! Enlighten, direct, save these souls you love!”

“Send saints and many evangelical workers, both men and women, to the Tuaregs, to the Sahara, to Morocco and to all those places where they are needed. Send holy little brothers and little sisters of the Sacred Heart there if it be your will!”

“Time not taken by walk or prayer is spent studying their language.”

“I have just finished translating the Holy Gospels into Tuareg language. It is a great consolation to me that their 1st book be the Holy Gospels.”

“Unite yourself to me, help me in my work, and pray with me for all these souls of the Sahara, Morocco and Algeria.”

“By the grace of the Beloved Jesus, it is possible for me to settle down in Tamanrasset.”

“I will stay here, the only European… very happy to be alone with Jesus, alone for Jesus.”

“To reside alone in a country is good. You have activity even without doing much because you become ‘of the country’.”

“Pray that a little good be done among these souls for whom Our Lord died.”

“This Africa, this Algeria and these millions of non-Christians cry so much for the holiness which alone can obtain their conversion. Pray for the Good News to arrive and that these late arrivals might finally present themselves at Jesus’ manger and take their turn in adoring him.”

“The country would need to be covered with men and women religious as well as good Christians who remain in the world so as enter into relationship with all these poor Muslims and instruct them.”

“Could lay nurses be found who have dedicated their hearts totally to Jesus and who consent and want to devote themselves for Jesus’ sake without either the name or the habit of religious?”

“Is my presence here doing any good? If it does not, the presence of the Most Holy Sacrament certainly does it greatly. Jesus cannot be in a place without shining forth. Moreover through contact with the natives, their suspicions and prejudices are slowly abating. It is very slow and very little. Pray so that your child does more good and that better workers than him might come to clear this corner in the field of the family’s Father.”

“My apostolate must be the apostolate of goodness. If someone were to ask why I am gentle and good, I must say, ‘because I am the servant of someone who is far better than me.”

“At the end of my retreat last year, burdened with the thought of the spiritual destitution of so many non Christians, I put to paper plans for a Confraternity of Catholic Association. The Confraternity that I named the ‘Union of the Brothers and Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus’ has a triple goal: to produce a return to the Gospel in the lives of persons of all conditions; to produce a growth of love for the Holy Eucharist; to give an impetus towards the evangelization of non-Christians.”

“The Tuaregs in my neighbourhood give me the greatest joys and consolations. I have excellent friends among them.”

“My work on the language is going well. The abridged dictionary is finished and its publication will begin in a few days’ time. The dictionary of proper names will be finished in 1914 along with the more complete Tuareg-French dictionary. I think that by 1916 I will finish the collection of poems and proverbs and by 1917 the texts in prose. The grammar book will be for 1918 if God gives me life and health.”

“I cannot say that I desire death. In the past I had longed for it but now I see so much good that needs to be done, so many souls without a shepherd, that more than anything else, I would like to do a little good.”

Tomorrow, it will be ten years that I have been saying Holy Mass in the hermitage in Tamanrasset and not a single conversion! It takes prayer, work and patience.”

“I am sure that what we need for the natives in our colonies is neither rapid assimilation, nor simple association, nor their sincere union with us, but progress which will be very uneven and will have to be sought by what are often very different means. Progress must be intellectual, moral and material.”

For two years, war had been tearing Europe apart. It was beginning to come to the Sahara too.

“450 km from here, the French fort of Djanet has been invaded by more than a thousand Senoussists armed with a canon and rifles. After their success the Senoussists have an open road to come here. Nothing can stop them except God.”

But God did not stop them and Charles was violently killed December 1 1916.

“Unless a wheat grain falls into the earth and dies, it remains only a single grain; but if it dies it yields a rich harvest.”